Dunstable in the First World War

How the Great War affected one small town, and how its local paper recorded the events.

By John Buckledee

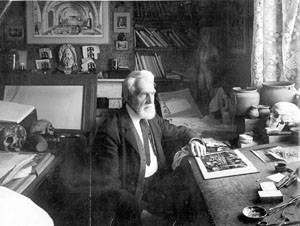

July 1914 and in Dunstable the Borough Gazette, under the proprietorship of Miles Taylor, was continuing on its tranquil and prosperous path. It was preparing to publish a third edition of The Maiden of the Bower, a Romance of the Chilterns by J.R. Freeman, and historian Worthington Smith had written articles for the annual Dunstable Year Book. There was no indication whatsoever that a catastrophic war was looming.

The paper, printed at its works in Albion Street using hand-set metal type and a hand-operated flatbed press, was continuing with its long-established method of buying in sheets of paper from London which had already been printed on one side with national news and features. The blank sides were then printed with local news and advertisements originating from the paper’s editorial office on the corner of Albion Street and High Street North.

Miles Taylor did not have the facilities in Dunstable to produce photographic plates, so any illustrations in the Gazette of the 1920s were on the pre-printed, London, sides of the paper. Just before war broke out, the pictures in the Gazette were from Manchester, Cambridge and Paris, where the big story was of the funeral of Harry Fragson, a popular comedian who had been murdered by his aged father.

So one of the odd aspects of the Gazette’s coverage during the war was that the sections of the paper printed in Dunstable would contain stories from the front line which updated the stories printed in London. Sometimes there would even be updates on the same page, when it would have been too time-consuming to alter an earlier story set, laboriously, letter by letter, by hand.

For example, one of the earliest Dunstable casualties of the war was Lieutenant Murray Benning, son of Dunstable’s town clerk, Mr C.C.S. Benning. The Gazette, in November 1914, printed verbatim a detailed letter from one of his fellow officers who described how Lt Benning had been wounded in the head by a bullet while serving in the trenches. It was impossible for him to be removed from the firing line for some time, but the officer shielded Lt Benning from further injury, being himself hit in the stomach by a piece of shrapnel while he was so doing. It took nearly three days for Lt Benning to be removed from the line. The officer, unnamed in the Gazette’s report, wrote that the lieutenant had subsequently received an operation on his wound and it was expected that he would recover.

Alas, further down the same page of the Gazette was a one-paragraph story reporting that Lt Benning had since died.

The outbreak of war clearly came as a great surprise in Dunstable. On July 29, the paper reported that the 5th Beds Regiment had set up camp at Ashridge, and companies from Luton, Dunstable and Leighton Buzzard were marching there for a fortnight’s training.

Church Street, showing the old drill hall opposite the White Horse public house. The hall later became the home of the Book Castle.

%20%20dmt%20024.jpg)

Dunstable's (new) post office in High Street North pictured in 1914 when it still had the builder's sign outside for G.B. Tutt and Sons.

131 High Street North (boarded when this photo was taken) - scene of the riot in 1914.

High Street North, Dunstable, pre 1914, looking from the crossroads. The building on the right was the town's post office until a new one was built in 1914.

Then, on August 5, different pages of the paper told of rapid and alarming developments. Belgrade had been bombarded by the Austrians, the training at Ashridge had come to a sudden end, and then “Members of the Dunstable company of the 5th Beds Battalion left the town this morning by the 8.16 train from Church Street station for Luton”.

Members of the Dunstable company who had been walking about the town during the day in their uniforms went to their drill hall in Church Street. A large crowd assembled there and it was announced that the company was to parade the following morning and then go to the headquarters of the South Beds detachment at Luton.

The newly built Dunstable Post Office remained open all night for the receipt of telegrams to reservists. Police leave was cancelled. Holidays for railway employees were abandoned. A serviceman who had been married in London at the weekend and who had come to Dunstable on his honeymoon received a telegram telling him to report for duty without delay.

Next week's Gazette, on August 12, vividly conveyed the rapid speed of events. There had been panic buying in the shops. Some traders had been profiteering. “Riotous scenes in Dunstable” said the headline. A large crowd had assembled outside the grocer's shop of Edward Mowse in High Street North. The house was stoned and the police had difficulty in preventing the building from being rushed. The police inspector called the army for help and, Major S.J. Green, commander of the Dunstable Squadron of the Beds Yeomanry, drove to the scene and addressed the rioters from the top of his car. His speech was reported verbatim by the Gazette reporter who clearly had excellent shorthand. “You know you do no good here,” said the Major, amidst various interruptions. The squadron was going on parade in a few hours time, he said, and added “I want to get an hour or two's rest before we go away and I make this appeal to you to go quietly home.” There were cheers and the crowd eventually dispersed.

The shop was at what is now 131 High Street North, near Clifton Road. There is only one MoWse in the 1914 Dunstable Street Directory – a Mr ERNEST Mowse at number 208, which under the renumbering of the street in 1921 became number 131. Given the difficulties under which the Gazette reporter must have been working, a mix-up in the shopkeeper's Christian name might well have happened. Certainly, the reporter was not able to speak to Mr Mowse to get his side of the story.

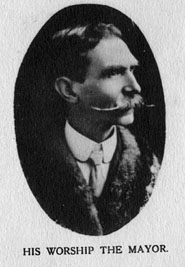

The excitement in town that week continued. Despite an appeal by the Mayor, Fred Garrett, for law and order, a large crowd gathered at Dunstable crossroads. Police remained on duty there and a decision was made to keep the street lights on all night. The only damage caused was the breaking of a shop window in Edward Street.

The paper published a letter from C.J. Hercock, of Great Northern Road, denying that he was a German spy who ought to be brought out into the Square and shot. “I am proud to be an Englishman,” wrote Mr Hercock, whose ancestors came from Rutland.

Messrs Waterlow's, the printing firm in Dunstable, promised to pay 10s a week to each employee while they were with the forces. There were already 27 Waterlow's men on active service.

The developing story continued in the same edition of the paper. The Dunstable men in the 5th battalion had assembled at the Plait Hall in Luton and then marched in the South Beds detachment to the railway station in Midland Road behind the Red Cross Band and the Chief Constable on horseback. Crowds of people accompanied them and many had the opportunity for a last handshake before the train steamed in. The Gazette reported: “Many of the womenfolk were in tears and many of the sterner sex must have had a lump in their throats when the band played Auld Lang Syne followed by the National Anthem.”

Outside Dunstable Town Hall during War Week 1914.

Dunstable Yeomanry, World War One

The original colour party, 5th Battalion,

Beds Regiment

High Street North parade – from a 1914 War Week booklet.

“Typical Dunstable recruits” – from a Dunstable War Week booklet 1914.

High Street North parade – from a 1914

War Week booklet.

The detachment left with about 16 officers and 430 or 450 men. Capt C.H.F. Metcalfe commanded the Dunstable company and its other officers were Second Lieutenants Baker, F.W. Ballance and E. Clarke.

The animated scenes at the London and North Western Railway station in Dunstable on the departure of the Dunstable Squadron of the Yeomanry was reported in the Gazette the following week. Its 142 men under the command of Major Green had been billeted at a factory formerly used by Messrs White and Son to make mineral water.

Army horses were also stabled there – a story in the same edition of the Gazette told of the inconvenience being experienced by traders, farmers and others in the district by having to part with their animals for the army at a moment's notice.

_r.jpg)

Three motorcyclists pictured in High Street North (Manor House on the left) in 1914. These are almost certainly the men who were the centre of a commotion at the Sugar Loaf Hotel.

There had been considerable excitement outside the Sugar Loaf Hotel that week when a crowd assembled following news that three German spies had been arrested there. The Gazette could not have missed that story – the Sugar Loaf stood directly opposite its office. It was all a false alarm – three young motorcyclists who had been questioning soldiers at the bar there turned out to be members of the City of London Cycle Corps.

But there was a real sense of paranoia. A “German spy” who had been seen resting under a tree in High Street South was a harmless traveller, but he was followed by a large crowd and had to be taken to the police station for his own safety. The hunt for a “spy” seen at Bedford led to all entrances to Dunstable crossroads being roped off so soldiers could stop and search vehicles passing through the town. Crowds gathered in the hope of seeing some excitement, but no spy was found. The son of Dunstable Alderman J. Boskett, working at a bakery in Watford, had to counter rumours that he was a German by displaying his birth certificate in the shop window. The only vaguely local justification for all this alarm was the arrest of a German soldier at Newport Pagnell. He had been in England when war unexpectedly broke out and had been trying to get home to rejoin his regiment. He was detained as a prisoner of war.

The man responsible for covering events for the Gazette, at least near the start of the war, was Mr William H. Press who has been described to me by one of the former printers in Albion Street as “an absent editor”. That is, he was employed by the paper's proprietor as a freelance and he worked from a house at 27-28 Great Northern Road, perhaps a lodging house. There were no bylines in the paper in those days but his name lives on in special articles he wrote for the annual Dunstable Directory, published by the Gazette. But he disappears from the street directory in 1914.

So much excitement, and then a period of calm. On August 26, the Gazette reported that the town had returned to its normal peaceful aspect, with little to remind it of the stirring times through which local residents had just passed.

But on September 2 there was a reference to “a gigantic struggle taking place between Allied forces and the invading German army” and the official war news being posted at the town's post office was being read by residents “with great interest”.

That week there was news of the first casualty among the town's soldiers. Private Benjamin Hedley Seabrook, who had been employed by E.J. Field, a cycle maker, at High Street North, and whose father was an insurance agent at 34 West Street, was killed at Catrawade in Suffolk. He had been on sentry duty guarding two bridges over the River Stour and was watching a troop train pass when he was hit by another train.

His death and funeral service at the Priory was reported by the Gazette in great detail, with the story taking up most of a page. Within a few months, alas, wartime casualties became so common that they were afforded only a few paragraphs of newspaper space.

A number of troops were still billeted in Dunstable, with a company occupying Burr Street School and others in private houses in the King Street area. The rifle range at the foot of the Downs was being constantly used for firing practice. Another huge influx of soldiers was reported on September 16 and all public buildings were converted into barracks. Quite soon there would be around 3,000 troops stationed temporarily in the town and residents began to appreciate the extra income provided as some kind of rental payment by “an officer with a bag of silver coins”.

The first Dunstablian to be wounded was Bernard Bliss of High Street South. The Gazette learned that he was in hospital in Southampton and reported on September 16 that he had been in the thick of the fighting. He had had “a very trying time”. His mother had three other sons serving in the forces one of whom, Frank, had been in the South African war where he had been taken prisoner by the Boers.

The Gazette had examined the casualty lists being published and concluded that the 1st Bedfordshire Regiment had been taking part in the fighting by the Expeditionary Force in France. One casualty was Captain R. Primrose Wells, second son of Mr A. Collings Wells of Caddington Hall. He had been wounded at Mons by a bullet in the leg.

The Gazette began publishing a weekly Roll of Honour on September 23 1914. It was a list of local men who had volunteered to serve in the forces and it expanded week by week as proud families sent in details to the paper.

And it was about this time that news of what had been happening to those individuals began to emerge. Marine E.O. Southwell, of Waterlow Road, whose parents had run the Cross Keys pub at Totternhoe, had survived a hair-raising battle at Antwerp where a petrol works had been set on fire and many troops were badly burned. Trooper A. Humphrey, of 21 George Street, had been fortunate to escape unwounded during the famous cavalry charge by the 9th Lancers at Mons, but had subsequently been wounded in the left thigh by shrapnel. Sgt Frank Wright, of 2 Icknield Street, had been wounded at Le Chateau and taken prisoner. Pte William Leach, son of the licensee of the Clifton Arms in High Street South, had been struck in the ankle by a shell fragment during what the Gazette called one of the “masterly retreats” from Mons. Pte William Horne, of Borough Road, was reported “wounded in action”. His mother, anxiously awaiting more news, was told by Pte Leach, now back in Dunstable, that he himself had picked up William Horne and put him in an ambulance waggon. Pte Leach later went back to the front and was promoted to sergeant. He was killed in March 1918 in France.

HMS Cressy

HMS Hogue

Three British cruisers had been sunk in the English Channel by what we learned later was just one German submarine. Aboard HMS Hogue was James Clarke, of 5 Tavistock Street, who had a wife and two young children. She had received a telegram saying “Regret James Clarke, No 5,105, not on list received of saved”. She was clinging on to a vestige of hope because the Daily Sketch had published a photo of survivors who had landed in Holland. One of them looked like her husband…

Mr G. Dolman, of Burr Street, a blacksmith aboard HMS Cressy which was sunk by that same submarine, had been rescued from drowning. The brief telegram to his family from the Naval Information Bureau said simply: “G. Dolman saved – N.I.B.” Mr Dolman, unusually for the time, did not want to speak of his experiences to the Gazette when he reached home. He was, incidentally, a member of the Dunstable Excelsior Silver Prize Band of which his brother, Mr W. Dolman, was conductor.

News of “titanic battles” was beginning to filter through. But it was just November 1914, and much, much worse was to come. The Gazette reported that the 2nd Bedfords were fighting at Bechelere, near a place called Ypres. It was the first mention of a name which became so infamous. The thousands of troops who had been billeted at Dunstable had left. There was news that the large force of Territorials who had been billeted at Luton had departed suddenly after surprise bugle calls had been heard throughout the town.

And on December 14, 1914, came a story whose opening words became chillingly familiar during the next three years. “We regret to hear that news has been received of the deaths of two Dunstablians at the front.”

They were Sgt John Brown, of 123 High Street South, eldest son of John Brown who had been Dunstable's town crier. Sgt Brown had been killed as long ago as October 26, “the place where he fell being unknown”. And Cpl Jeffrey Tearle, of Alfred Street, had been killed by a bullet on November 1. His mother had still not been informed officially, but had learned of his death in letters from the friends who were at the front with him. In those early days of the war the troops were fighting alongside their childhood chums from their home town.

As the war progressed, there was a change in the way the war news was reported. In the first few weeks the soldiers at the front had sent letters home giving massive details about where they were, with whom, and how many men were in their battalion. The letters were passed on by proud parents to their local paper, which then printed them verbatim. Who needed German spies when the papers were so full of information?

It gradually came to a stop, with the lads at the front making a point of saying “I must not tell you where I am now”. But still, Lance Corporal Boswell wrote to his mum in January 1915 saying that they had spent three days and three nights up to their knees in mud and water and “it was awful to see old comrades shot down by my side. We hear not a word about how the war is going. We have lost one colonel and one major, killed in action, and we have only 400 men left out of the 1,100 who went out with us”.

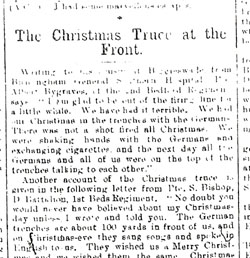

And the paper on January 13 told of that extraordinary Christmas truce, when soldiers on both sides held an unofficial ceasefire. Pte Albert Bygraves wrote home: “There was not a shot fired all Christmas. We were shaking hands with the Germans and exchanging cigarettes and the next day all the Germans and all of us were on the top of the trenches talking to each other.” And Private S. Bishop, of D Battalion, Ist Beds Regiment, wrote: “The German trenches are about 100 yards in front of us and on Christmas Eve they sang songs and spoke in English to us. They wished us a Merry Christmas and we wished them the same. Christmas morning they were quite happy and shouted and told us not to shoot, and to play the game straight, and they would come out of their trenches and meet us halfway. We agreed, and I and some pals went out and shook hands with them. They gave us some cigarettes and one of them gave me a fine cigar which I enjoyed on Christmas Day.”

The Gazette remained busy, interviewing everyone in the small community who had sons or husbands at the front and giving everyone a pretty good idea of what conditions were like on the battlefields. The flow of information was much more open than it is today.

For instance, Gunner Harold Bliss, of 46 High Street South, sent home a German shell, eight inches high and painted red and blue, which he had picked up after the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. The Gazette, on March 24 1915. reported that the souvenir “enables one to realise more fully the terrible havoc which must be caused by the explosion of a projectile even of the size of this one”. And Private Christopher Smith, wounded at Ypres where he had taken part in a bayonet charge, had arrived home and gave the Gazette a gleeful account of how they had tricked the Germans by digging a false trench around which they had left a collection of tins attached to long pieces of string. When they pulled the tins, the rattling noise had tempted the Germans into an attack. “We allowed them to proceed as far as the wire entanglements and they were then mowed down by heavy and effective fire.” Letters such as this were passed on to the Gazette which printed them in full.

The postal service was clearly very efficient, even though letters from the front often brought bad news. The grandmother of Sgt Reginald Fearne, of 1 Winfield Street, Dunstable, learned of his death in a letter from his Quartermaster Sergeant rather than from an official telegram. Corporal Frank Mead, of 6 Albion Street, Dunstable, in a letter to his mother revealed that Private Sidney Bright, of Chalton, had been killed beside him.

The Dunstable Gazette did not have the technology to make plates to print photos, unlike the neighbouring publication at Luton. Photos of individual casualties became commonplace in the Luton News. They were sent to the newspaper office by relatives. One week, the paper printed a notice expressing astonishment at learning that one grieving mother was trying to save half-a-crown to have her son's photo printed in the paper. The paper indignantly said that it did not, of course, make a charge for this.

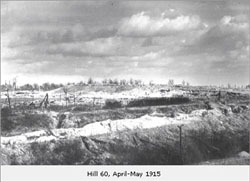

Hill 60, April-May 1915

The Gazette's editorial column, now devoted almost every week to its opinion on the war, perhaps gives a feeling of the mood of the town. In January, it comments that the statement by Lord Kitchener that the war is “only now about to begin” might seem folly to some but it “manifestly embodied a certain truth”. The paper went on to say that opinion was steadily ripening in favour of some form of national service as there were no more voluntary recruits to be found. On May 5, describing the German attacks as “a frenzy of despair” it comments: “The war is now unquestionably entering upon its most critical stage.”

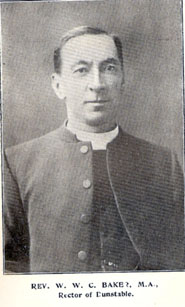

The Rector of Dunstable, Canon Baker.

The Mayor of Dunstable, Fred Garrett

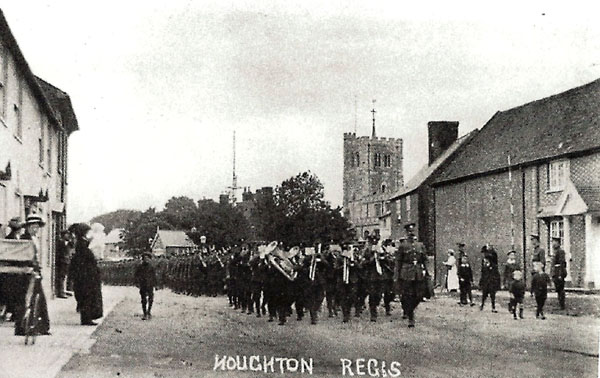

Incidentally, Capt Charles Baker, the Rector's son, was serving in the 1st 5th Bedfordshire Battalion which was just about to take part in a three-day route march - 60 miles in full war kit - across the county, with crowds thronging the streets of the towns through which they passed. It was a historic march, with everyone perhaps sensing that they were saying farewell. The men paraded outside Dunstable town hall and went on to Houghton Regis where they bivouacked for the night on Houghton Green. Most of the men slept in the open in their greatcoats, on top of waterproof sheets and blankets, but someone found a tent for the officers. There are splendid pictures of the men's arrival in Luton which give a vivid idea of the scale of the march.

The First 5 th Bedfords on parade in George Street, Luton, 1915.

Marching through Houghton Regis

Meanwhile, thousands more soldiers had arrived in Dunstable. The Gazette reported rumours that they were coming and within days the men of the Notts and Derby battalion had set up what the paper called “a canvas city” on the northern outskirts of the town, between Brewers Hill Farm and the Watling Street. In true local paper tradition, the paper was soon reporting on a football match featuring the Sherwood Foresters.

And the Gazette got on with the business of reporting the aftermath of the riot in town on the week war broke out. Bedford Standing Joint Committee had considered a claim for compensation under the Riot Damages Act by a Dunstable trader, unnamed in the Gazette report but we can guess who it was. It was suggested to the committee that the tradesman had brought the trouble upon himself, but the committee members felt that this had nothing to do with the issue before them. They awarded him £7 15s 9d compensation. To put this in proportion, in 1914 the maximum wage for a printer on the Gazette was 10s a week.

The spirit of enterprise was alive and well. There were still advertisements in the papers for fashionable hats but, more appropriately for the time, the Paris House fashion shop in Luton was advertising black mourning clothes, which could be altered and despatched within a few hours of purchase. The well-known local auctioneer Chas Allcorn had a front-page advertisement in the Gazette offering to sell insurance for damage caused by Zeppelin raids and other damage caused by aircraft. There had been a report of a Zeppelin raid at Folkestone but bombs dropping on Dunstable?

Worthington Smith, pictured in 1907.

Worthington Smith, pictured in 1907. In June 1915 there was a recruitment march through the area, with the aim of finding 550 volunteers. This time, there was no rush to join up and the recruitment officer, Captain F.W.F. Latham, was disgusted to find only 50. He made a speech describing his experience at Caddington where they were told that there were some 15 young men who were a disgrace to their country for not taking their share of what he described as “the work to be done”.

The recruiting detachment marched to Caddington on Bank Holiday morning and found a dozen or so young men playing football on the village green. They ran away and by the time the troops had fallen out not one of the young men were to be seen in the village. Two of the men were later found in a public house, said Capt Latham, but not one of them would come back and do his duty.

Lt Berlin's funeral, Houghton Regis.

Chequers corner, Houghton Regis, scene of Lt Berlin's accident. The pond has now been filled in.

Chequers corner, Houghton Regis, scene of Lt Berlin's accident. The pond has now been filled in.

Sgt P. Ives (left), died of wounds May 9 1915

Sgt R.A.R. Fearne, killed on April 30, 1915.

At about the same time, for instance, there was quite a short article reporting the posthumous award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal to two Dunstable men. Sgt Percy Ives, of Downs Villa, Great Northern Road, had rescued a number of wounded soldiers during a reconnaissance mission. He had later been captured after being wounded and had died in a German hospital. Sgt R. Fearn, whose death had been reported earlier, was awarded the DCM for his gallant conduct under heavy bombardment in defending a shell crater on Hill 60. He had been killed while doing so.

Their pictures, interestingly, were published in a Dunstable Year Book issued by another Dunstable printer, James Tibbett, and used by permission of the Luton News. The Gazette, under Miles Taylor, still could not produce photographic plates. The Luton News, being in business competition with the Gazette, certainly would not have allowed its plates to be used in a Gazette publication.

But the people producing the Gazette were clearly beginning to flag under the pressure of work. At the start of the war they had begun printing a Roll of Honour - a weekly list of Dunstable Volunteers and their regiments. But by now the paper was noticeably failing to update the list regularly with details of the casualties reported elsewhere. Among some letters from soldiers at the Battle Front, saying how much they appreciated receiving copies of the Borough Gazette with news from home, was one from Sapper T. Walker, of St Peter's Road, pointing out that his name was not on the list! The Gazette promised to put that right – but it was three months before the printers got round to doing so.

Meanwhile, the men of the 1/5th Bedfordshires who had marched so proudly through the county in June were, by August, fighting the Turks. First indication of this in the Gazette was a letter home from Lt F.W. Ballance, of Dunstable, who had been wounded while fighting in the Dardanelles. “We had a terrible time,” he wrote. “We had to attack a hill and were met by a hail of bullets and shrapnel…The place is infested with snipers who are painted green to match the bushes and one hardly ever spots one of them.” Lt Ballance was wounded by a bullet but escaped death because it had first hit his mess tin.

The first indications of what the Gazette called “the battalion's terrible baptism of fire at Gallipoli” is reported in the paper dated September 8, 1915, two or three weeks after the event.

“From letters received from local men it appears they have been in the thick of the fighting which followed the surprise landing at Suvla Bay,” reported the Gazette.

Sgt Major Edgar Odell at the Grammar School with Cadet Jeffs in later years.

Sgt Major Odell had written to his wife at Ashton Road from a hospital in Cairo saying “we have had a hot time” and that he had been hit on the Sunday and had to lay there until Tuesday morning when he was found.

His letter added: “We unfortunately lost Capt Cumberland and Capt Baker, and several other officers, before I went down.”

And that was the way news of the death of the son of Canon Baker, the Rector of Dunstable, was broken.

Private Sidney Hutchins, of 19 Alfred Street, wrote home from a hospital in Alexandria saying he had been hit by shrapnel and then shot by a sniper. “Our lads made a charge with fixed bayonets, and under Canon Baker's son, and I fully believe they caught it rather hot,” he wrote.

And Private W. Abrahams wrote to his mother at 1 Borough Road that his friend George Finch, of 98 High Street South, had been shot down during a charge on the Turkish trenches led by Colonel Cumberland, who had also been shot dead. The Gazette reported that Pte Finch's mother had not been officially informed of his death.

Capt Baker

Capt Brian Cumberland.

Lt Col Brighten

Next week, the Gazette printed a letter home from the commanding officer, Col Edgar Brighten, saying that Cumberland and Baker led their companies, which were in the front line, magnificently. The latter had his arm shattered but went on till he dropped. He added: “Poor old Menkin, my little brother Dick, Lydekker and Rising were also pipped…”

“Menkin and Rising, I'm sorry to say, we could not find. That is the awful part of this country, it is thick with scrub and we can only move about at night so it's next to impossible to find them. All said, it's no use mincing matters, those booked as missing must be dead,”

A memorial service was held at the Priory Church that month to remember the lives of 15 Dunstable heroes, including Lt Baker. The service was conducted by Canon Baker but the Gazette report made no special mention of his son. Many subsequent histories of the Gallipoli campaign have noted that he had died in an extraordinarily brave bayonet charge followed by men from the same small community who had been baptised and perhaps married by his father. No-one wanted to let their friends down.

Pte Finch

Pte P. Holliman, of 300 High Street North,

died of wounds received at Gallipoli.

Pte F. Smith, of 95 High Street, Houghton Regis, was killed in action at Gallipoli.

Pte F. Smith, of 95 High Street, Houghton Regis, was killed in action at Gallipoli. On January 19 1916 the Gazette headline was Bedfords Under Fire. Heavily Shelled and Gassed. Another Kensworth Hero Killed in France This referred to Sgt V. Woodcraft had been hit by a stray bullet. The Gazette also reported an extraordinary incident at Bedford where a shell brought back from France had exploded at the J and F Howard iron works, killing two men and two boys.

The same issue carried the first of what became a series of letters describing the war against the Turks from Driver C. Cowling, of The Cottage, Church Street, Dunstable, who was writing from a place behind a big hill “as big as Blow's Downs”. He gave details of a skirmish in the desert with Bedouin tribesmen. The Arabs had fired at the British from the hills, the British batteries had replied and then the cavalry had charged, killing 200 of the enemy. Unfortunately several cavalrymen were killed when their horses fell into a deep cave during the charge.

The domestic news was dominated by a series of court cases where the authorities were enforcing new lighting regulations designed to minimise Zeppelin attacks. A long series of motorists were fined for using headlights at night and householders for failing to black out their windows.

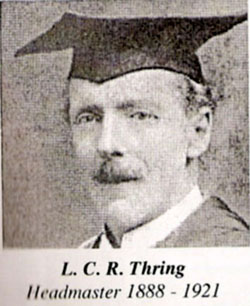

L.C.R. Thring, headmaster of Dunstable Grammar School, 1888-1921.

The Gazette reported in considerable detail the embarrassment of the headmaster of the Grammar School, Mr L.C.R. Thring, who was a magistrate but had to appear before his own bench for failing to screen a window at the school. He pleaded not guilty, saying that he had taken every possible precaution, but two special constables said that light from the school had lit up houses on the other side of the street. Mr Thring was not fined but had to pay costs of 16s.

Charlie Chaplin Coming To Dunstable was another headline that week, early in 1916, reporting that a two-reel comedy by the great comedian was to be shown at the Cinema Theatre opposite the town hall. And there was the heaviest fall of snow for many years. There had not been anything approaching the fierceness of this since the great snow storm of 1877, said the Gazette, reporting the plight of some Dunstable girls who worked in the munitions factory at Luton and who had been stranded when their train coming home became stuck in a drift. They eventually walked back to Dunstable and “but for the frequent assistance of the men in the party many of the girls would have been sorely tried”.

The Defence of the Realm Act was used for a prosecution of a Studham villager for ringing the church bells there at night. He had merely been examining the bells for a fault and the case was dismissed on payment of costs.

In May the Gazette had to reduce its size to six pages, and dropped its pre-printed national news and its page devoted to lists of Dunstable men serving in the forces. It got worse in 1917, when the paper reduced its size to four pages and announced that it would print its news in much smaller type to try to include as many stories as possible. The shortage of labour was making it extraordinarily difficult to keep the paper going, it said, and the mills producing newsprint were so short of staff that some had closed.

Its domestic news was dominated by weekly reports of the Dunstable Tribunal where appeals were heard for exemptions under the Military Service Act.

These could be fierce occasions. One conscientious objector, the 29-year-old manager of a straw and felt hat manufactory, was told by the tribunal's chairman, the Grammar School's Mr Thring: “I do not think you are worthy of the name of a man.” Another tribunal member, Col Fenwick, told the appellant: “I think it is very dangerous to have such a man as you about the country.” The man was found liable to service in the forces, but was exempted from combatant duties.

The Gazette staff was clearly uneasy, despite the jingoistic tone of its weekly editorials. One reporter, who had his own unsigned column for a few months called “Leaves From A Reporters' Notebook”, criticised the Tribunal for sending a gents outfitter, aged 39, into the forces. The reporter described him as “a delicate young man” who was far from being fitted for the life of a soldier in any way.

The editorials, by the way, were unswervingly patriotic in their support for the British war leaders. In 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, the comment was: “These stirring days represent the most glorious ordeal in our history.”

The more human view of the war was represented in a report of The Great Battle by a letter from Pte Fred Griffiths of the machine gun company who wrote home saying that he was covered in mud and hadn't shaved for days. Pte Griffiths told his family that he had got some nice souvenirs, German helmets, rifles and bayonets, but he had got tired of carrying them around and had thrown them away. But he had kept a postcard he found on the body of a dead German which he had sent back to Dunstable.

The Gazette reported that this was a pathetic Christmas greeting showing a photo of a wife and three children in their home standing beside a decorated Christmas tree with the words “God preserve our father, far from us in the land of the enemy”.

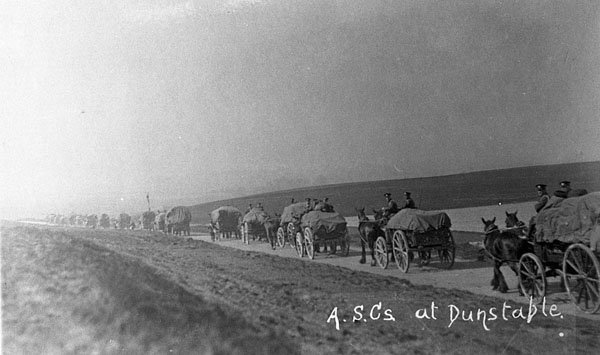

The Army Service Corps carrying supplies through Dunstable. The Green Lanes are in the background.

The Army Service Corps carrying supplies through Dunstable. The Green Lanes are in the background.

Army Service Corps heading down the Tring Road.

There were numerous medals and awards being reported. Captain Jock Henderson, of Scotby House, Great Northern Road, was awarded a Military Cross for gallant and conspicuous service in the field. He had been in France since November 1914 and had been through all the “shows” including the hardships of that first winter in the trenches. He had built what the Gazette called the now-famous “Duck's Bill” under heavy fire…this was the name for a salient in the British trench positions which became the focus of fierce fighting. And Commander Chas Stuart Benning, a son of the town clerk whose other son had been killed in 1914, was awarded the DSO in recognition of his gallant work in connection with submarine warfare.

But more and more the news was sombre, and no amount of patriotic prose could disguise it. The wounded and dead were listed under headlines like “Dunstable Men Fallen In The War” or “The Toll Of War”. One soldier, with two gold stripes on his uniform indicating that he had twice been wounded, approached a policeman in Church Street, Dunstable, saying that he had forgotten his name and address and did not know where he was. He was taken to the police station where the inspector's wife looked after him. He had wandered to Dunstable from a hospital in Nottingham.

A young woman pushing a pram threw herself under a military lorry passing through Dunstable near the Square. She survived but her suicide attempt caused great consternation in the town. The paper, which gave her name and full address, (Mrs Baxter, 42 Victoria Street) said she had not recovered from her husband's death at the Front some eight months previously. Pc Tearle carefully tended her 12-month-old baby until proper care could be found and the wife was taken to Three Counties Asylum. Her other child, a ten-year-old boy, was found a home.

L/Cpl Ernest Banks, of Capron Road, who had joined the Territorials in 1914 and had been invalided from Gallipoli with dysentery, had been killed at the Battle of Arras. His family, not knowing of his death, had send him a food parcel to France and received a letter from his comrades saying that they had shared the food and “should any of us by God's grace be allowed to return to our loved ones and should be in your district we will call and see you.”

The sister of Pte Leonard Franklin, son of the bandmaster of the Borough Band, received a letter from his Corporal who had found his body, shot through the heart. There were no documents to identify him apart from an envelope with his sister's address and a letter from his friend Archie, of Church Street, Dunstable. The corporal enclosed a three-penny piece which he had found on the body and which he thought, if you were a relation of his, you might like something to keep.

The town was enormously affected by the distress of Mrs Alice Smith, a widow, of Clyde Villa, Victoria Street, whose two dearly loved sons, her sole support in recent years, were both in the 4th Bedfords. Her son, William, had been awarded the Military Cross for carrying messages under heavy shell fire. But just a month after this news was announced she received a letter from him saying that his brother, Ernest, had been killed by a sniper. He wrote: “At the first chance I went and found out where he lay and had him fetched in.” William had helped to dig his grave, under fire, and laid him to rest.

The next week, on May 9, 1917, a soldier comrade of William's wrote to a Dunstable lady asking her to break the news to Mrs Smith that William, too, had been killed.

Mrs Smith later received a letter of sympathy from the Queen saying that the circumstances were “inexpressibly sad”. Mrs Richard Gutteridge, wife of a prominent Dunstable citizen whose son, Lt Gutteridge, died from wounds later on in the war, arranged for a car to take Mrs Smith to a ceremony at Kempston where her son's posthumous medal was presented to her.

There was great sadness, too, for the Grammar School headmaster, Mr Thring, whose son, Second Lt Ashton Thring, had died of pneumonia following influenza while based at Ripon in Yorkshire. Ashton Thring, aged 20, had been a brilliant scholar of whom great things were expected. His military funeral at the Priory Church was reported in great detail.

The German U-Boat blockade of the British Isle was having a devastating effect, and by 1918 the food shortage and meetings of the Dunstable Food Committee were dominating the news. Women flocked to the town hall to apply for tickets for margarine. A crowded meeting at the same venue listened with attention as a councillor explained the details of food rationing – a new concept for the townspeople.

Totternhoe council wrote to Dunstable saying there was almost a complete absence of provisions in the village. And there was considerable excitement at Dunstable cattle market when a Luton butcher arrived with authorisation from the Admiralty to purchase the first 24 beasts available. But there were only seven up for auction. The speedy arrival of a Food Committee Officer prevented the situation from getting out of hand…he knew enough about the small print to rule that the Admiralty Priority Certificate was invalid because there was no surplus beyond local requirements.

The great German offensive of 1918 was first mentioned in the Gazette in March of that year. “Never before has there been a battle of such magnitude,” said the Gazette, and there were unprecedented lists of casualties in its columns, week after week, month after month. The Rector of Dunstable lost another son, Second Lt Avaling Baker, who was killed in France. Also among the many killed was Sgt Arthur Mead, of 82 Edward Street, who had survived Gallipoli; Pte Clifford Banks, son of the licensee of the Sugar Loaf hotel; Lt Blunden, son of the proprietor of Dunstable's Primrose Laundry; and Pte Maurice Jarman, son of the Pastor of the Old Baptist Church in St Mary's Street. There were appeals in the Gazette from parents seeking news, however unofficial, of their missing sons. And, sometimes, there was relief when a postcard was delivered from a German prisoner-of-war camp saying that sons or husbands were, at least, alive.

One such arrived for Mrs Creamer, of Union Street, from her son. He had been wounded in 1914 and discharged, but called up for service again in 1917, wounded, returned yet again to the Front and was then listed as missing. Then came the welcome postcard saying that he was a prisoner in Germany.

There was sad news about Lt M.W. Dickens, a former Dunstable Grammar School boy who had joined the Royal Flying Corps. He had taken off into thick fog, despite having engine trouble, and had not been seen again. The Gazette reported that parts of his aircraft had been found at sea by a French destroyer.

The Gazette's editorials, which for four years had been unwaveringly optimistic, became more subdued. Then, on September 11, the mood changed. The paper commented, with a clear sense of relief and wonder, that anyone who had suggested a few weeks ago, with the Germans in sight of Paris, that the enemy would be sent reeling back would hardly have been believed. They had said many times before that the end was in sight and now it was really true.

But the casualty lists continued, under such routine headlines as “News of Dunstable's Wounded” or “Casualties At The Front”.

We now know that the war ended at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month. But with no radio or television, Dunstable first heard the news when a train arrived from Luton crowded with people cheering and waving flags. The Gazette on November 13, with its headline saying simply “PEACE !” reported that there was scarcely a house in the town which did not display some sign of the great rejoicing.

But it also reported the deaths of Sapper Thomas Ward, of Victoria Street, and Sapper Fred Isaac, of Great Northern Road. Both had died of malaria in Egypt. Imagine the feelings of their families who, in the very week of peace, were confronted with the very worst of news.

END...