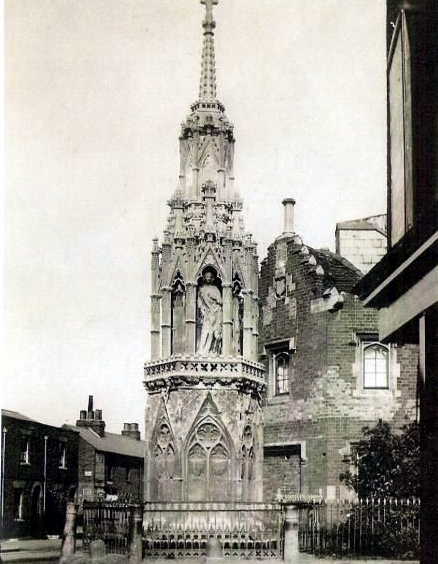

Near here once stood a tall and lavishly decorated stone column, known as an Eleanor Cross. It was one of 12 monuments erected by King Edward I in memory of his wife, Eleanor of Castile.

Queen Eleanor died near Lincoln on November 28 1290 and her body was brought to Westminster Abbey on a journey which took 12 days. The grieving king ordered that an elaborate memorial should be raised at every spot where the queen's funeral procession had halted.

One of these was at Dunstable, which the king and queen had visited many times. The coffin containing the queen's body rested on a bier in the middle of the town's marketplace before being taken to the Priory. The king's chancellor and nobles then decided on an appropriate spot where a cross "of admirable size" would later be erected. The Prior of Dunstable sprinkled holy water to bless the chosen place.

Stone masons and sculptors worked for around two years, from 1291 to 1293, to create the monument. It included effigies of the queen and other carved decorations.

The Eleanor Cross remained a local landmark until the English Civil War. Dunstable was on the border between areas controlled either by the Royalists or Parliamentarians and was damaged by soldiers from both sides. Roundhead troops wrecked the memorial in 1643 and nothing above ground has survived.

It is therefore difficult today to identify the exact location of the Cross, particularly as the layout of the crossroads and the site of the market have changed substantially over the years.

Old documents indicate that the 14th century Red Lion Hotel, which stood on the corner of Church Street, was built very close to the Cross. When the Cross was reduced to rubble, more buildings grew up around the site, eventually almost straddling the crossroads and reducing the main road to two narrow lanes. One of the new houses was erected "against the Red Lion" by a draper named Richard Fisher (c1628). Many years later this had fallen into disrepair and was part of "waste land" used by the Duke of Bedford to provide a Market House "to keep people from the rain". The Duke's 1738 lease records that this land included part of "the late demolished cross".

The Market House was once of a cluster of buildings demolished in 1803 to make way for the busy stagecoach traffic of the time. A replacement Market House was built in High Street North and converted into a town hall in 1866.

William Nicholls, a schoolboy in Dunstable in 1790, described many of the things which he had witnessed in his lifetime in his pioneering book on local history, Dunno's Originals, whose first sections were written in 1821. He said that when the high street was improved in 1803, ponds were filled in and houses removed from the middle of town. When this was being done, workmen uncovered what were claimed to be the foundation of the cross, set around with oak posts in a circle, at equal distances. This was near the entrance to the Rose and Crown (todays Taylor's estate agent on Keep's corner), south of a building called the Cross House.

The Cross House, also known as the White Lyon, stood astride the crossroads, facing towards London, and was alongside a house or pub called The Peacock.

More clues to the location of the Cross are provided by a 1541 bailiff's list of properties in Dunstable in which the widow of J. Kente is recorded as paying rent for land next to the Cross in Southstrete (High Street South). Also in Southstrete, Roger Barber Jnr had a tenement on the east side at a corner next to the High Cross in the middle of the town.

The 1541 list also records Wm Leonard as being a tenant in Whites Lane next to the High Cross in the middle of the town. Whites Lane seems to have been the very narrow road between the houses in the middle of the crossroads and the Red Lion.

The legal documents, however carefully they were worded, are not precise enough to pinpoint exact locations. The guess is that the foundations of the Cross lie under the crossroads, near the Church Street exit.

One further mystery is that the Eleanor Cross is almost ignored in the medieval diary kept by the canons of Dunstable's Priory monastery. The canons record the arrival of the queen's body and the way in which its resting place was reserved, but there is nothing else about the creation of such a major landmark in the town. That's very curious.

Text: John Buckledee of Dunstable and District Local History Society. ©

Design: David Turner.

Narration: Alistair Brown of Dunstable Repertory Company.

Recording: David Hornsey.

Website developer: Joshua Buckledee.